Coaching feedback

What should a coach focus on: outcomes or activities?

Recent experiences from a coaching course

About this article: we have two versions, this one is for those of us who are primarily interested in motorcycle safety and high performance riding; we have another version which is more targeted at continuing professional development (CPD) and medical educators. There are some interesting parallels but feel free to flip back and forth to either version.

I recently went to a high performance motorcycle course, where we were coached intensively on techniques for the race track. My own racing days date back to decades ago, skittering down icy slalom courses. I have no intention of becoming a motorcycle racer (plus my wife would kill me) so why on earth do such a course?

Simply put, this is a great place to learn and practice higher level skills in a safer environment. Safer?? Absolutely:

no oncoming traffic

all the safety gear (including an air bag vest and armor)

no potholes, gravel, ice/mud/cowshit - just clean dry pavement

no surprise obstacles such as tractors, cars pulling out of side roads

fewer things to hit if you are sliding down the track after a lowside

These are things that make life "interesting" (and shorter) for the motorcyclist on the road. Removing them means that you can focus on the things you need to when riding, allowing you to try push yourself and your bike a little harder, with fewer distractions, and much more safety if you exceed your limits.

There was an intense amount of coaching, and numerous different evaluation and feedback methods. I came away from the course as a much better and safer rider. But looking back on the course, and the methods used, I realized that there are many parallels to my day job in teaching. While there have been many improvements in Continuing Professional Development (CPD) and adult learning over the past years, there are clearly things we can do better.

So what is different?

Analogies between motorbike tracks and CPD

Thinking back on the differences, the key factor is that, in CPD, we focus on outcomes and not what people are doing. This is like the motorcycle coach saying to me, "your laptimes are ten seconds slower than your group."

When I ask, "Ok, coach, what do I do to drop my laptimes?", he would just say, "Ride faster".

This sounds so obvious. And yet, so much of our "data-based feedback" to students boils down to just this:

"Your prescribing costs are too high"

"You request too many x-rays"

But we do not provide timely data about what students are actually doing in practice. As a comparative example from the motorcycle course, there was a dramatic highlight in the day which shows the differences.

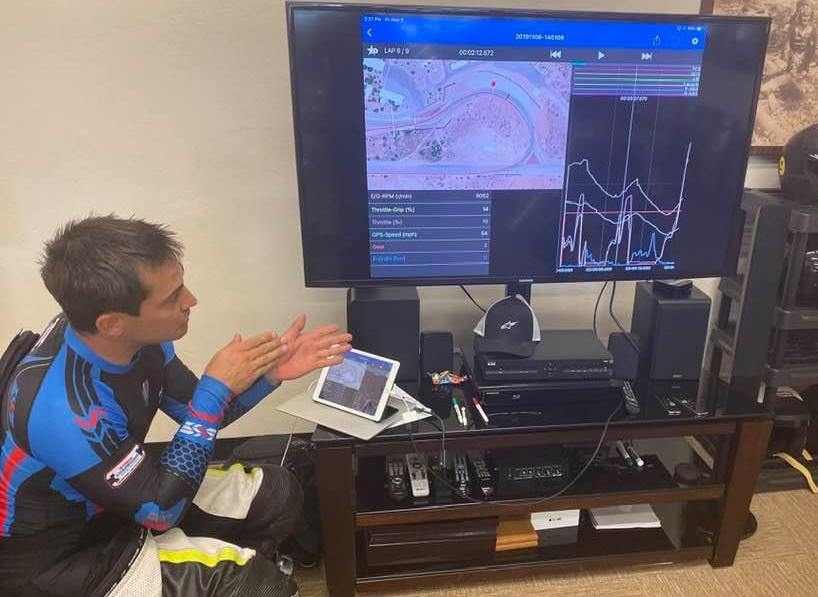

We got to ride a telemetry bike, loaded with sensors, for 2 sessions of 3 laps each. After each session, we sat down with the coach and he showed us in fine detail just exactly where and how much to brake on the course, with graphs showing us exactly what we were doing wrong, and comparing with the graphs of experts, which clearly showed a better way to brake.

The second session showed an immediate decrease in laptime of 5 seconds (the outcome data), but it was more helpful to see the improvements in the braking patterns and timing. This made so much more sense. This is what made the difference and improved the outcome.

Now, the magic of the sensor data was that it provided metrics that the coach cannot see. For many of the other sessions, we also received feedback from a coach and/or videocamera riding directly behind us. And yes, they can tell, from the brake light, the on/off status of your brakes. But that pales in comparison with a sensor that measures the exact amount of pressure being applied to the brake pads at any given moment.

This trivial difference may not seem important to a non-rider, but learning to use your brakes well, in every situation, at any speed or lean angle, is crucial to your very survival. A learning rider can only brake at 0.5g, whereas a skilled rider or average car can stop at 1.0g (and the top MotoGP riders will achieve 1.5g).

We can do better in CPD by providing more timely feedback on what people actually do in a given situation rather than averaged outcomes. Even specific examples lose their point when delayed by 3 months: look at how little effect photo radar tickets have on driver behaviour, compared with being pulled over by a cop.

How do you get to Carnegie Hall?

As in the old joke, practice, practice, practice

In many of our educational sessions, we take great care to present information in interesting ways. We like our learners to be engaged; but we rarely measure a change in behaviour, and we rarely follow up to see if our lessons are retained.

We rarely provide opportunities to practice on similar cases. In one particular course, they do have a reflective element to practise and opportunities to discuss. Many of the elements that we praise as being essential components of adult learning are there. And, for those of us with young brains, hearing it once is enough.

But for those who have been in practice for a while, this new information hits the barriers of skepticism, poor memory, inertia etc. Or, if the information is presented too early on to students, it seems irrelevant ("I'll never see a case of that…").

Practise is obviously more important when there is a dynamic element in the coaching scenario. But what about other less dramatic elements of professional practice? As noted above, staged reminders and repeated opportunities to practice still help. Such staging and repetition lie at the core of the evolution in language teaching, seen in programs like Rosetta Stone.

Other types of feedback

What other kinds of feedback did we have at the motorcycle course? We reflect on these, not because it was the ultimate in adult learning, but because they used many of the same techniques that we currently use in CPD, and so some comparisons may be helpful.

Self-rating scales

After each set of laps, we had to reflect on how we felt we had just done and complete a simple paper scale.

This is one of the most commonly used assessment methods because it is easy and cheap to do. On our course, it did have value in that it made you think about what you planned to work on in the next set of laps. If you don’t go out with a plan, improvements will not magically happen by themselves. But the approach lacks any kind of objectivity.

Coach verbal feedback

After each set of laps, you might receive some pointers from one of the coaches.

"Your tires are cold. It will take at least a lap for them to warm up and provide good grip."

There was a really good 1:2 coach:student ratio, which helped but, as the course directors pointed out, you must seek out the coaches and make it useful to your own needs. All the coaches were very experienced riders but not all were very experienced coaches. However, there is such a gap between coach and rider that any small tidbit is gratefully received.

Peer verbal feedback

An unanticipated type of feedback that was noticed was that of peer commentary.

"Your riding is really smooth... not aggressive… smooth… great for the road…"

This was a group of riders who were all highly vested in their own success, but more importantly, you were not competing with each other and there was no incentive to outdo the other guy. It was more of a cooperative game. It was in each rider’s interest to see everyone do better. Not only was there a positive feeling from helping each other, it also made each rider’s job easier if they had to spend less time dodging around those who were struggling. The rising tide floats all boats. This form of feedback was very informal, but clearly influenced some riders, mostly to the positive.

Still photos

We had a professional photographer who patrolled the track on each day.

These pictures were useful in reminding us of certain key points. For example, it is important to turn your head, eyes and shoulders towards where you want to go. In the shot above, you can see that the rider has only turned his head and eyes to the right. Ideally, the shoulders and torso should also be more rotated across the tank towards the exit of the turn. This is easier to see in a still image than in a video.

The photographer was every experienced, knew the track and his audience well. At first, you would assume that his job was to make us look good: nobody wants to buy pictures of themselves looking like a klutz. However, he was quick in providing previews of his pictures throughout the two days.

Certain things like upper body position, knee position and placement of your bike on the track are often easier to see when things are distilled down to a single image.

Pillion ride

We had an opportunity to ride pillion with one of the more experienced instructors on the course. With the aid of strong grab ring positioned on the tank of the bike, you were able to brace yourself and yet adapt to a useful riding position.

While a bike with two riders has more inertia, for most of us it was a reminder of how much further the bike could safely lean in the apex of a corner, and how much harder the bike can be pushed, provided that you are smooth with the controls.

Really exhilarating but more importantly, a strong sensation of just how much more grip is available in a tight turn, rather than just seeing this on video.

Video feedback

The highlight for most riders were the video feedback sessions. As usual with video sessions, you tend to be your own worst critic. Getting past the false modesty is key. The most important things to focus on are the flow of movements, in comparison with the still shots mentioned above. The still photo simplifies and clarifies certain things. But most of your actions are a dynamic series of coordinated activities: when to shift your weight, when to turn into the corner, what sort of line are you riding through a corner compared to the experts.

Key points could be frozen for comparison or easily rewound. Each of these sessions was highly valued but of course it is also costly. Each student typically received 2-3 video sessions over the two day course. More would be great but this is not practical within the economics of the course. There was some value to be gained in watching each other’s videos. Many of us have similar errors and it helped to have this reinforced while watching others.

One of the most valuable exercises that we had on the bike course was when the instructors placed traffic cones at random points on the course, forcing you to change your line and speed with little notice. This was a great exercise for road riding where you never know what you are going to find around the next corner. Being able to brake hard and safely mid-way through a curve is something that has helped my road riding enormously.

Insta360 video

As a personal experiment, I also took special video camera with me and bolted it to the bike for a few laps.

This camera is designed to record a full 360 degree panorama view in high resolution all the time. There is no such thing as missing the shot because the camera was facing the “wrong direction”. Action cameras, like GoPro, with their very wide angle of view have become very popular since 2002, because you do not have to carefully align the camera with what you want to capture. This is true, but even more so, for a 360 degree camera.

The software that comes with the camera has some additional useful features. You can fix the point-of-view in a certain direction. It remains the same no matter where the camera housing is facing. You can also change the playback angles afterwards, allowing you to focus on certain actions or body position issues, or on where you are on the track, or what is happening around you.

Because all of these perspectives are captured all the time, you can also review multiple perspectives of the same sequence of corners. You do not need to do this often but it is invaluable for isolating certain problems that are hard to see for the coach or video bike riding close behind you.

Telemetry data

In a special session, I was given the opportunity to have a few laps on a telemetry bike. This was not part of the regular course. At first, I was hesitant believing this to be aimed at top racers where every millisecond counts. Not me.

I am so glad that they persuaded me to try this. Even for a less skilled rider klutz like me, this made an enormous difference. We had two sets of three laps on the telemetry bike, with a review of the data immediately after each session. The bike had sensors to measure the following parameters:

Brake pad pressure

Throttle position

Throttle response

Lean angle

Speed

Gear

Position on the track

Other parameters are also measured but these are the useful ones for the coach. The first three are particularly useful. The short video below gives a slightly better sense of how this works:

When a coach or video camera is riding behind you, they can tell when your brakes are on/off from the brake light and they have a rough idea of how fast you are decelerating. Having the exact tracing of how smoothly you apply the brakes and when this happens during the turn is amazingly useful, even for an intermediate rider klutz like me.

A key component of the course was learning a technique called trail braking, where you trail off the brakes as you lean more into the turn. Getting this right makes you much more stable and allows you to compensate for all sorts of surprises, both on the track and on the road. All riders should learn this technique.

Because, in a panic situation, we all have a tendency to grab the brakes too roughly, this is one of the commoner causes of a rider going down. Repetition, in a safe environment, is essential: to the point where it becomes second nature.

While track practice and coaching give you some idea of how to do this well, the coach is guestimating your actions much of the time. Being shown in precise detail exactly what you are doing is so much more effective. In only two sessions, my trail braking improved dramatically. This saved my bacon on some subsequent road rides, with rapid changes of tire grip and road surface. Such things became “interesting” rather than sphincter puckering.

Throttle action is less likely to throw you off but the same principles apply. Smoothness matters, with gradual application of the throttle as you decrease lean angle.

Discussion

The session with the telemetry bike got me thinking about how we tend to apply feedback on performance in clinical situations. We tend to focus on outcomes, not actions. As noted at the start, this is like using laptimes, and the accompanying instruction to “ride faster”.

Most learning systems merely capture completion of an activity, along with a single percentage pass mark. That is like going back to high school math tests and relying on whether little Johnny got the right answer, not whether he used a correct approach in getting to that answer.

Breaking this down, our outcomes-based feedback is delayed (photo-radar tickets), averaged, subject to influence by many factors beyond our control and rather non-specific. Doing more than this has previously been seen as impractical. But we now have the tools available to measure what our learners actually do, and when they do it. We can move beyond the generalized conclusions, which we know are subject to bias. Our teachers are keen observers, able to detect subtleties. Just don’t expect them to be consistent, unbiased judges. And don’t just tell them to “ride faster”.

Last updated